Coteaux du Layon: Decline & Recovery

In this, the second instalment of my guide to the Coteaux du Layon and its wines, I continue my exploration of this vineyard’s history. For detail on the origins of this vineyard, its early history as it grew under the patronage of influential Dutch traders, and the story of both river and vineyard up until the arrival of phylloxera, head back to the first instalment, my Introduction to the Coteaux du Layon.

A number of the best slopes of the Coteaux du Layon remained abandoned after phylloxera, and it could be argued this is still the case today, more than one hundred years later. This was especially true of the very steep slopes on the right bank, where the Corniche Angevine rises up 60 or 70 metres above the Layon, sometimes with an incline of 40%. Those vignerons with the energy and resolve to plant anew found they preferred the flatter land on either side rather than the coteaux directly overlooking the river. The reason was simple; it was much easier to work, and this shift away from the slopes was only reinforced in the latter half of the century when the tractor became widely available.

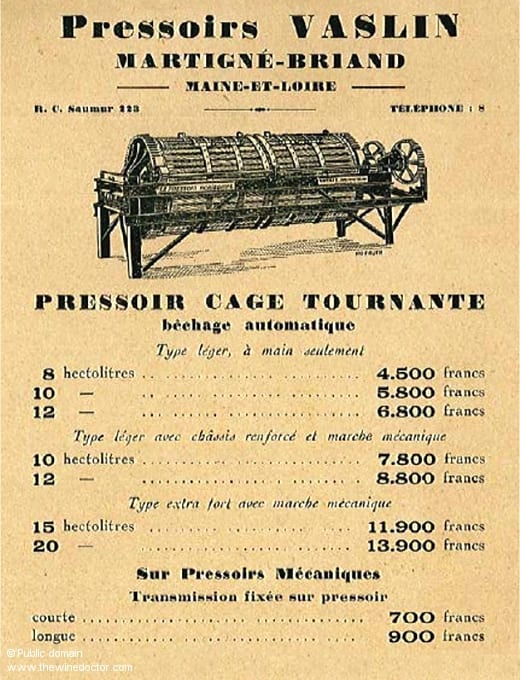

Life in the cellars of the Coteaux du Layon was also changing. At the turn of the century a new piece of kit, a cage press first developed in 1858 by a local man named Joseph Vaslin (1800 – 1876), began appearing in the cellars along the Layon. The Vaslin family, Joseph being succeeded by son and then grandson, would serve the region’s demand for wine presses during much of the 20th century. By the 1920s their press was automated, a feature which only enhanced its popularity; a price list from Pressoirs Vaslin (reproduced below), circa 1924, reveals the range of possible sizes and level of automation that was possible (and it also reminds us that there was a time, otherwise unimaginable, when there were single-digit telephone numbers).

The Vaslin cage presses were extremely popular, and by 1925 there were 2,000 in use in local cellars. With time, however, the business outgrew the family, and it was acquired by Gaston Bernier, another local who hailed from Beaulieu-sur-Layon. It was Gaston who took the business global, working from a newly built factory at Chalonnes-sur-Loire, where the Loire and Layon meet. Pressoirs Vaslin would grow to become the modern-day firm of Bucher Vaslin, now renowned across the wine world for their presses and other winery equipment. By the end of the 20th century this factory, which stands on the Rue Gaston Bernier, was responsible for the production of 60% of the wine presses in use across the world.

Please log in to continue reading: