Loire Valley Wine Guide: Geology

The Loire flows from its source, deep in the south of France (surprisingly close to the Rhône Valley and Burgundy in fact), for 1012 kilometres before it drains into the Atlantic. For much of this course there is hardly a vine to be seen; aside from the high outposts of the Côtes du Forez and Côte Roannaise, the waters of the Loire have completed half of their journey to the ocean before they pass a vineyard which happens at Sancerre, the first of the truly great Loire Valley appellations. All the well known vineyards and regions of the Loire – Touraine, Anjou, Saumur and Muscadet – are strung out along the next 500-or-so kilometres. Unsurprisingly, with such a long and winding course, there is considerable variety in the geological features the river encounters. And as with any other wine region, geology – a vital component of terroir – is one of several key factors that determine the style of the wines produced along the banks of the Loire.

Thus some examination of the geology of the Loire Valley is warranted. I must first acknowledge, however, that each of the wine regions mentioned above have their own distinctive geological nuances, and thus I will provide more detail on the specifics of the relevant geology – or terroir, if you prefer – for each region and appellation in turn. My purpose in bringing the geology of the Loire Valley into this introductory section of my guide to the region is to provide a general overview, as this should help in understanding why some regions possess such radically different terroirs to others.

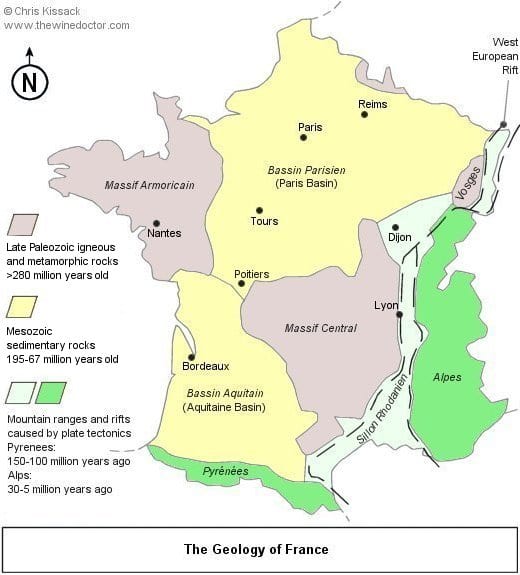

For this very broad overview we can divide the course of the Loire into three sections. First we have the river flowing from its origins in the Auvergne, where the vineyards of the Upper Loire can be found. Here the waters are running over the Massif Central. As the river heads north it comes off these ancient rocks onto the Bassin Parisien, eventually looping round at Orléans and then coming down towards Tours and Saumur. Here, therefore, we have the Central Vineyards and those of Touraine, Saumur and the eastern part of Anjou. Finally the waters leave this basin to weave their lazy way over the rocks of the Massif Armoricain, host to the vineyards of the western part of Anjou and Muscadet. I will look at each of these geological sections in turn, starting at the top with the Massif Central.

The Massif Central

The Massif Central does not play a huge part in the geology of the Loire vineyards, nevertheless it certainly cannot be ignored. The vineyards of the Côte Roannaise, Côtes du Forez, Côtes d’Auvergne and Saint-Pourçain are all gathered here. The Massif Central is a mountainous region vaguely triangular in shape, the tip to the south (pointing towards the vineyards of Roussillon), the base to the north, very roughly on a line drawn between Dijon and Poitiers. The detail of the geological evolution of this part of France is complicated (too complicated for me anyway) but suffice to say the rocks here are of very ancient origin. They date back to the Paleozoic and Precambrian eras, which together describe some of earth’s earliest history, the rocks being in many cases 280 to 350 million years old (and some are much older than that), and they are largely igneous and metamorphic. The former are created from cooled volcanic magma, a prime example being granite, the latter are created when pre-existing rocks are exposed to extremes of pressure or heat, such as the creation of gneiss, orthogneiss and schist from shale. For more explanation see my introduction to the Geology of Bordeaux which includes a generic basic introduction to geology with regard to all France.