The Muscadet Story

The identity of the wise individual responsible for first planting the vine in these lands, washed with sea spray and blow-dried by Atlantic breezes, isn’t known. That hasn’t prevented various authorities on the subject coming up with a few theories though, occasionally fanciful, sometimes less so.

You can’t have a French wine region without at least a little hint of Roman origins, and Muscadet is no exception to this rule (which, I confess, I have just invented). Some have asserted that the first vines may have been planted on the orders of Emperor Probus. This is certainly not impossible; the arrival of Roman culture anywhere in Europe, from the precipitous slopes looking down onto the waters of the Rhine to the rolling pastoral landscape of England, very frequently involved the planting of vines. Nevertheless, the evidence for Probus having made such a diktat seems far from cast-iron.

Despite this uncertainty it does seem that the vine and wine had a presence in this region during the centuries that followed, as evinced by the writings of the monk Saint Hermeland (c.640 – c.720). Hermeland lived on the Île d’Indret, just downstream of Nantes, and he wrote in considerable detail on the importance of the vine and its religious significance. Even better evidence for the presence of the vine comes from Saint Martin (c.527 – 601), whose antics – mostly escaping divine retribution, avoiding being turned to stone and establishing monasteries – I have already described in some detail in my profile of Domaine des Herbauges. He was indeed responsible for the founding of the monastery at Vertou, southeast of Nantes, and of course every good monastery needs a vineyard. Wine was not only relevant to religious ceremonies, but could also be an important source of revenue, so it should come as no surprise that Saint Martin was quick to plant some vines.

The Dukes of Brittany

It might seem strange to think of the Muscadet region so strongly influenced by the beliefs and actions of the Breton nobility, Brittany being some way to the north, well beyond Nantes, and extending out to the north-western tip of the country. But Brittany as we know it today, a distant corner of France, is a relatively modern creation, its current boundaries having been drawn as recently as 1941. Prior to this it was larger, perhaps 25% more expansive than it is today, and it incorporated the modern-day Loire-Atlantique département, including Nantes and its vineyards. These borders reflected its ancient origins; Brittany was only absorbed into France in 1532, prior to which it was the Duchy of Brittany, a feudal state the capital of which was Nantes. Legacies of these ancient Breton origins persisted through to relatively modern times. Writing in Topographie de Tous les Vignobles Connus (Bouchard-Huzard, 1866), André Jullien dealt with the wines of Nantes and the surrounding vineyards in his chapter on Brittany, as I have already described in my Introduction to Muscadet.

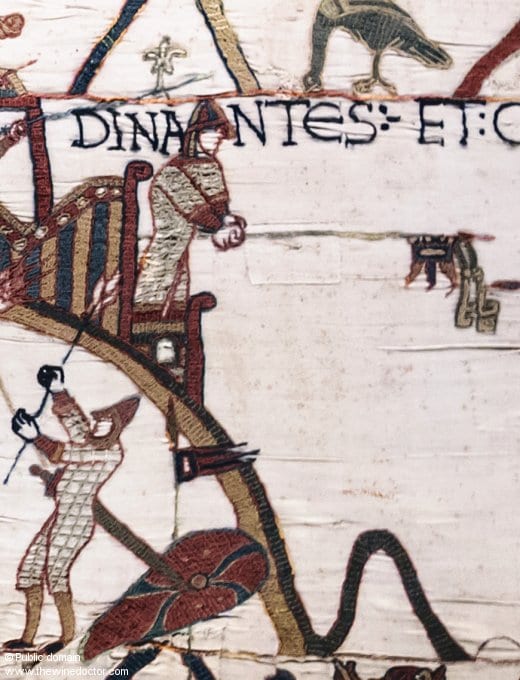

During the 8th century there was active trading of goods, including wine, between the region and the Celtic countries to the north, particularly Ireland. In the years that followed Alain Barbetorte (c.900 – 952), Duc de Bretagne, was a passionate advocate of viticulture, encouraging further planting. A successor to his title was Conan II (c.1033 – 1066), perhaps best known for his appearance in the Bayeux Tapestry. Conan II of Brittany and William of Normandy had gone to war in 1064; this didn’t go well for Brittany, and by 1065 Conan II was forced to take refuge in Château de Dinan, a fortified keep not far from the coast. Besieged by William and his army, he eventually surrendered the keys to the château, allegedly handing them over on the end of a lance, a scene immortalised in the famed tapestry (pictured).